Raud Mirgadirovis an award-winning Azerbaijani journalist and political analyst. In 2005, he was named the Honored Journalist of Azerbaijan. In 2008, he received the Gerd Bucerius Free Press of Eastern Europe award for achievements in the development of independent media. A former political prisoner, he is currently living in exile in Europe.

Raud Mirgadirovis an award-winning Azerbaijani journalist and political analyst. In 2005, he was named the Honored Journalist of Azerbaijan. In 2008, he received the Gerd Bucerius Free Press of Eastern Europe award for achievements in the development of independent media. A former political prisoner, he is currently living in exile in Europe.

“The truth is always implausible… To make the truth more plausible, it’s absolutely necessary to mix a bit of falsehood with it. People have always done so.”

Fyodor Dostoyevsky

In all his speeches since the Second Karabakh War, Ilham Aliyev has stated that the conflict has been resolved. He is trying to convince us that the trilateral statement signed on November 10 is in fact Armenia’s capitulation, and that the future status of Nagorno-Karabakh is no longer under discussion and will never be on the agenda again. In his words, it is a “corpse.” However, neither the Prime Minister of Armenia Nikol Pashinyan, nor the Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, nor the Deputy Chairman of Russia’s Security Council Dmitry Medvedev, agree with him. Some might say that Pashinyan’s opinions should not be taken seriously, his goose is cooked. But what about the latest statements from Lavrov and Medvedev? Can we disregard them and what they say?

Dostoyevsky is one of my favorite writers, perhaps my absolute favorite. But I only partially agree with the things he said. In my opinion, in terms its impact on people’s beliefs and on socio-political processes, truth does not matter. What shapes the attitudes of every individual and society as a whole is not what happened in reality or how it happened, but something else entirely.

More important in terms of its impact on conflict resolution is what we are willing to accept as truth and why. This can be demonstrated on the basis of modern trends: more important is what the forces that have the ability to manipulate public opinion and human psychology want to sell us as the truth, and why. “Even the sun looks blue when you look at it through blue glass,” wrote Jalal ad-Din Rumi.

THERE IS NO TRUTH

In other words, there is no such thing as absolute truth or absolute justice in real life. I know that most religious believers will not agree with me. They believe in the existence of absolute truth. In fact, there is one or sometimes several counter-truths for every truth that influences our minds and emotions and causes us to act. Each counter-truth is accepted by some other individual or society as the absolute truth. At first glance, we are witnessing a clash of opposed truths and concepts of justice. In fact, it is a clash of fairytales, legends, and myths that individuals and societies believe in and which they try to convince others are true.

If there really were an absolute truth, humankind would have long ago found a way to develop without conflict.

Let’s take a close look now at the impact of all this on the settlement of the Karabakh conflict. There are two sets of fairytales, legends, and myths that we and the Armenians believe in and which we present as truth to the international community. Interestingly, it makes no difference which set the international community believes in. The important thing in terms of its impact on the settlement of the conflict is something entirely different. The main goal is to convince the centers of power that determine the position of the international community that to demonstrate belief in the authenticity of one or another legend, fairytale, or myth would further their geopolitical interests. In this case, the forces we are talking about will use all the military, political, legal, and informational means at their disposal to convince the entire international community of the veracity of a particular legend, i.e. to promote a version of the conflict that suits their interests. Only then can small states such as Azerbaijan and Armenia achieve solutions to the conflicts they are involved in that accord with their interests.

I would like to recount here an incident that took place in the late 1990s, told to me by the former head of the Secretariat of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan, Eldar Namazov. At that time, most experts were convinced that the world of international relations would be unipolar. Everyone saw the United States as the center of power that would rule it. That is why the young people around Heydar Aliyev tried to convince him of the need to expand cooperation with the United States. According to Eldar Namazov, one day the president listened to them attentively (many admit that the ability to listen attentively to others was one of Heydar Aliyev’s distinguishing features) and said: “Do you really think I don’t understand that the Politburo is in Washington now?” For young readers I should explain that the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the USSR was a body with real power where decisions were made on all the important issues. The Politburo held its meetings in the Kremlin in Moscow. At the time, the Kremlin competed with the White House in Washington for influence in international relations.

Fortunately or otherwise, I cannot say, but the United States did not become the only center of power in a unipolar world. Today, the United States is the first and foremost center of power to have a say in shaping the world order, but it is not the only one. Today, there are still secondary centers of power – China and Russia – which present themselves as equal partners of the United States in a future multipolar world order. In the current era, China and Russia have been quite successful in competing with the United States in regulating a number of conflicts, especially at the local, i.e. regional, level.

The United States, as the main superpower, considers the whole world its sphere of influence. However, due to limited capacity and resources, it is not equally influential and well-represented in every region. At least for now, China does not consider the South Caucasus to be within its sphere of influence. Russia, however, sees the South Caucasus as its traditional sphere of influence and has the capacity and desire to compete with the United States in the region. If the geopolitical interests of Russia and the United States coincided in the region, it would not be difficult to find a complete or long-term solution to the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. But the problem is that from a geopolitical point of view, not only do their interests not overlap, but I would even say that they contradict each other. Therefore, any attempt to resolve the conflict by one of these centers of power is opposed by the other. It may sound cynical, but in terms of the powers with geopolitical interests in the region and the current world order in general, it does not matter what the interests of the parties to the conflict are or who is right. Only the interests of the centers of power determine which of the legends offered by the parties to the conflict will be believed, which will be accepted as the truth. This explains the calls of the parties to the conflict to the international community for truth and justice. This is an important part of the game, because the appearance of justice is a very important element of the process of this or that solution gaining acceptance among the conflict parties and the international community. But it is both ridiculous and dangerous for the parties to the conflict to expect justice in response to their appeals or to believe that that is even possible. Geopolitical powers are not interested in justice, but rather in what they will gain from the resolution or the continuation of the conflict. In other words, they are interested in what we can give them in return for its resolution. The myths, fairytales, and legends that hold us captive prevent us from facing and accepting the bitter, inevitable reality. In some cases this can lead to tragedy.

WE SHOULD FREE OURSELVES FROM MYTHS

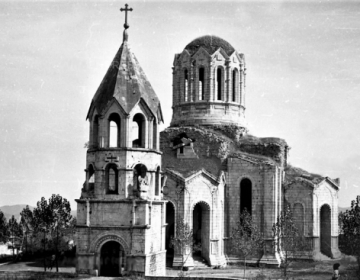

The “most important” myths that both Azerbaijanis and Armenians believe in and promote to others are historical. Armenians consider Karabakh “historical Armenian lands” and we consider it “historical Turkic lands,” and both sides sincerely believe their myth to be absolutely true.

I would like to share with you my memories of an event that I witnessed and participated in after the events of August 2008. I was attending an international conference in Ankara on conflicts in the post-Soviet space. Obviously, the events in Georgia were the focus of the conference. Experts representing the parties to the conflict tried to convince us, depending on their ethnicity, that the territories occupied by Russia were either “historical Abkhazia,” ”historical Ossetia”, or “historical Georgia.” Most of the speeches were historical disquisitions. For the first time in my life I heard very interesting facts about the ancient Ossetian state, which arose in the caves of the Caucasus mountains and flourished in those same caves. But after a while, I felt tired of these endless historical disquisitions. You know why? I remember some time ago a very heated and emotional argument between Armenian and Azerbaijani historians on social media. They were arguing in all seriousness about the “ethnic identity” of the female jawbone found in the Azykh cave. I should point out that Azykhantrop, who lived about 350,000-400,000 – or by some estimates 500,000 – years ago is considered to be one of the oldest human remains in the world.

I did not intend to speak at the conference, but when I was given the floor I spoke about these debates between Azerbaijani and Armenian historians over the female jawbone found in the Azykh cave. Coincidentally, a well-known Armenian political scientist Alexander Iskandaryan was sitting opposite me. We have known each other for a long time. Mr. Iskandaryan was an Armenian political scientist who took a relatively pragmatic position on the settlement of the Karabakh conflict. At the end of my short talk, I addressed him: “Mr. Iskandaryan, since you are a homo sapiens, you probably won’t claim the jawbone found in the Azykh cave.” Luckily, he didn’t. If he had, it might have brought on the apocalypse…

All joking aside, let’s get to the heart of the matter. The point is that, in my opinion, reference to the historical past cannot have a positive impact on the resolution of conflicts we face today, if only because the realities of yesterday and today are different. Trying to substantiate the claims of any society to this or that territory by referring to history is one of the most unconstructive paths that could be taken.

What does it mean to be historical Armenian or Turkish lands? First, try to look at the matter from a religious perspective. People who believe in eternity should consider themselves guests in this world. How can you claim that the place you are visiting is yours from the dawn of time to the end? How can you interfere in the judgment of the Creator? I do not intend to. Therefore, I never delve too deeply into this subject.

To substantiate their claims to Karabakh, Armenians refer primarily to ancient sources, while we refer to historical documents from the last few hundred years. Armenians claim that Azerbaijani Turks are “savage nomads” without a homeland, while we claim that Armenians resettled in the region in the last two hundred years. I have no intention to conduct a historical study. I will rely only, exclusively on common sense. But I would like to note that manifestations of ethnic racism are clear in the claims of the Armenians.

Based on the principle of historicism, all of the North and Central American states, most of the South American states, Australia, and even Egypt have no right to exist in their current ethnic composition. Neither the British, nor the French, nor the Latinos, nor the Arabs can consider these territories their historical lands. This reality is enough to destroy all the historical arguments of both Armenians and Azerbaijani Turks.

However, I will speak about a number of other secondary myths that are actively used by the parties to the conflict. One of the arguments we use the most is that the Armenians determined their destiny once and for all when they created the Republic of Armenia, which is itself in historical Azerbaijani lands, and therefore they have no right to create a second Armenian state. It must be admitted that this is a very weak argument. Just look at how many Arab and Anglo-Saxon states there are, and I haven’t even mentioned the two German states in the heart of Europe yet. However, these facts also prove that a shared ethnic origin and religion is not a sufficient basis for “miatsum.”

In addition, I would say that the Armenians use geopolitical myths to substantiate their claims to Karabakh. In essence, these myths are based on the image in the international public consciousness of the Armenians as a “suffering nation”. Armenians want to convince the international community that their physical existence as a nation depends on how this conflict is resolved. In other words, they want to convince the whole world that “savage nomadic Turks are trying to exterminate us for the second time in the last hundred years.” They are trying to use the “guilt complex” which arose in the West and in the Christian world as a whole after the tragic events that took place in Turkey during WWI. “You once sacrificed us for your geopolitical interests. Don’t do it a second time,” is the message they constantly employ when appealing to Western public opinion. They likewise use Islamophobia, which became a dangerous trend in the Christian world after 9/11 and is the banner of all nationalist populists. “We are the last “Great Wall of China” that protects the cultural Christian world from savage Muslim aggression,” is one of the main slogans of their international propaganda campaign. It is no accident that from the first days of the Second Karabakh War, Armenia accused Azerbaijan of using mercenaries from the Middle East in military operations. I mentioned earlier that all these accusatory myths benefit from the ideology of ethnic and religious racism. Here I would like to draw attention to only three points. First of all, with the exception of Russia and France, the world’s leading powers did not take these accusations seriously even for the sake of appearances during the 44-day war.

Secondly, Armenia, which seeks to stoke Islamophobia in the Christian world, has forged much closer relations with Iran, some Arab states, and Islamic organizations, which a number of Western countries have accused of financing international terrorism, than Azerbaijan has.

And finally, Armenia, which declares itself a “Great Wall of China” for the Christian world, does not take into account its neighbor Georgia. Georgia, which presents itself as an Orthodox Christian state, is actively cooperating, and in fact building strategic alliances, with Azerbaijan and Turkey, which Armenia characterizes as sources of Islamic extremism. In addition, unlike Armenia, there are Turkic and Muslim communities in Georgia. Orthodox Christian Georgians do not see Azerbaijan or Turkey, nor the large Turkic and Muslim communities in Georgia, as a threat to their physical existence.

THERE ARE NO RULES

One of the biggest myths that the parties to the conflict make reference to is the norms of international law. Every time official and unofficial representatives of Armenia and Azerbaijan refer to the norms of international law, I have to force myself not to laugh, and I recall the famous saying of the immortal Mashadi Ibad: “If I have a fault, it is my faultlessness.” We can apply this logic to the system of international law in force today and say with full confidence that “the only rule is the absence of any rules.”

There is popular quote that diplomacy consists of petting the dog and until the muzzle is ready. It is said that this phrase is 150 years old and today nothing has really changed in international relations.

170 years ago, Russia helped the Austrian Empire suppress the Hungarian uprising for independence, after which people began to call Russia “the gendarme of Europe.” It is said that the author of the term was the Russian Emperor Nicholas I himself. He was proud of Russia’s reputation as the butcher of the peoples fighting for freedom. Is the foreign policy of the current President of Russia, Vladimir Putin, a successor of Nicholas I, any different from that of his predecessor? In fact, we have let the Russian Army, which we persuaded to leave our country with so many hardships, back into Azerbaijan. And we did it willingly.

I will be told that this is the 21st century, not the 19th. There are norms of international law. Russia can no longer behave like a “rabid dog” against peoples with the desire for freedom. Look at Ukraine, Georgia, Moldova. In violation of all existing international law, Russia occupied Abkhazia and South Ossetia and recognized their independence, annexed Crimea, and shamelessly refused to withdraw its troops from Moldova, despite Moldova’s demands. Russia considers itself the gendarme of the post-Soviet space.

The main thing that allows Russia to behave shamelessly is the lack of any imperative rules governing international relations (specific rules of conduct must be defined and enforced). Recall the norms of international law that the parties refer to in connection with the Karabakh conflict. Azerbaijan is trying to prove the supremacy of the principle of territorial integrity, and Armenia is trying to prove the supremacy of the right of peoples to self-determination. In fact, whether we like it or not, neither of these two principles is imperative as a legal norm or a generally accepted rule governing international relations. If the principle of territorial integrity were imperative, dozens of new independent states would not have emerged in Europe, Asia and Africa in the last 30-40 years after the collapse of the world colonial system in the middle of the last century.

But Armenia itself understands and accepts very well that the right of such peoples to self-determination is not imperative as a norm or a rule accepted in practice. Otherwise, Armenia would have long ago recognized the independence of Nagorno-Karabakh, followed by Abkhazia, South Ossetia, the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, and Kosovo, as well as the annexation of Crimea.

Unfortunately, there is only one rule to solving any problem in international relations, and it is not based on any legal norm. If the interests of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council coincide, any problem can be solved. In such a case, they can make the parties to the conflict accept the supremacy of any norm of international law. But lately, their interests almost never coincide. In all other cases, the state of a conflict changes based on the interests of the leading centers of power at that time, and on the capacities and resources that they can allocate to solving the problem. In other words, anyone who can tries to get their slice of the pie.

I would like to draw attention to an interesting aspect of all this. Even within individual leading centers of power, there is no unified approach to resolving such conflicts. Despite the fact that the vast majority of Western countries recognize the independence of Kosovo, several members of the European Union considered it unacceptable. These states do not recognize Kosovo’s independence because they accept the imperative of the principle of territorial integrity, but only because they are dealing with separatist movements themselves.

I can give another example. The European Union, which does not have a unified position on Kosovo’s independence, has unequivocally supported the Spanish government in its fight against Catalan separatists.

Prior to the 44-day war, Karabakh was the only conflict in the post-Soviet space that Moscow was not directly involved in and could not moderate single-handedly, mainly because there were no Russian military forces in the conflict zone. Today, Russia has the opportunity to independently moderate the regulation at least of the current situation in the Karabakh conflict. To be precise, we gave this opportunity to Russia ourselves. We must also take into account that in the South Caucasus Russia does not want to see any state, including Turkey, as a partner.

Now we are engaged in the creation of a new myth. We claim that the Karabakh conflict has ended, the topic has been closed, and the issue of the territory’s status is a “corpse.” We are trying to convince ourselves and others of the truth of this myth. The fact that there is no peace agreement and that Armenia and Russia do not agree with this new myth is not a serious problem. The danger is that there is no guarantee that this myth, which official Baku is promoting in order to create the illusion for the public of complete and absolute victory, will come true. This is a very serious danger.

Unofficially, experts are working day and night to create another myth. It is in Azerbaijan’s interests for Pashinyan to remain in power because it is very likely that a weak Pashinyan will make concessions. That is a reasonable probability, but I have a rhetorical question: after the deployment, with our consent, of Russian troops in Karabakh, when Moscow has the capacity to independently moderate the settlement of the conflict, to whom will Pashinyan make concessions – Putin or Aliyev? This is followed by non-rhetorical questions: What will Putin demand from Aliyev in exchange for Pashinyan’s concessions? To what extent will these demands meet the interests of Azerbaijan? We have handed the key to the resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict to Putin’s Russia, at least for the foreseeable future. Whatever happens in the near future will primarily be in Russia’s interests.

According to Nietzsche, people live and work not for the future, but mainly to preserve their past. Aliyev is in fact living by this principle. He has not taken into account that the results of the 44-day war are already yesterday’s realities. The realities of today and tomorrow will be determined not by Aliyev’s wishes and the myths he promotes to his people, but by Russia’s military and political presence in Karabakh. By convincing people of myths which are unlikely to come true, the President of Azerbaijan may repeat the mistake to which Pashinyan fell victim. After the ceasefire agreement was reached in 1994, the Armenian people were absolutely convinced of the truth of the myth that “the Karabakh conflict has already been resolved.” Therefore, the political leaders could not even discuss any peace option that did not meet the expectations of this myth. According to Charles Maurice de Taleyrand, one of the greatest diplomats of the 19th century, a politician must excite the people in such a way that he can use them as he pleases. But a real politician should not fall prey to the public excitement that they stimulate. That path leads both the politician and the people into the abyss. In other words, it is necessary to regulate the level of public excitement. Aliyev’s claim that “the Karabakh conflict has already been resolved” is very dangerous because it does not reflect the reality we may face in the future. In fact, the possible outlines of this reality will be determined not by Azerbaijan and Armenia, but by Russia. At least in the near future…

In short, in the near future we face a “no-holds-barred” contest with all the rules set by Putin’s Russia. The question is, is it possible to free ourselves from Russia’s claws? Yes! It is possible if Russia suffers a shameful defeat in some new Crimean War, as in the middle of the XIX century. In that case, Moscow would lose the capacity and desire to behave as the sole owner of the post-Soviet space, as in the 90s.

This new reality will usher in new rules of the game…

pia.az