Thousands of dead and worries over the welfare of prisoners complicate efforts to build a lasting peace between the two nations

By Ann M. Simmons

The Wall Street Journal Jan. 29, 2021

Last October, Yusif Budaqov, a young sniper fighting in Azerbaijan’s army in the battle for Nagorno-Karabakh, was killed two weeks after his 23rd birthday, one of thousands of casualties in the conflict with Armenia.

His family still mourns him, plastering their home with photos of his childhood and early military days. There is little prospect of reconciling with Armenia now the fighting is over, said his mother, Latafa Budaqova.

“It’s not possible,” she said. They “came to our land and our children are dead because of them.”

For years, Azerbaijan and Armenia have been at loggerheads over their conflicting claims to Nagorno-Karabakh. The enclave is internationally recognized as part of Azerbaijan but was controlled by ethnic Armenians for almost three decades.

Last fall, Azeri forces reclaimed swaths of the territory. A subsequent truce brokered by Russia in November aimed to end the dispute over the mountainous enclave for good.

A burned truck sits on the side of the road in Kalbajar district, Azerbaijan.

But the scale of the losses on both sides and deep-seated enmity make it difficult to move on and rebuild the shattered province, leaving it a tinderbox not just for Azerbaijan and Armenia, but for the broader stability of Moscow’s traditional domain in the South Caucasus.

Some 2,855 Azeri soldiers were killed during the six weeks of fighting that erupted on Sept. 27, according to the country’s Defense Ministry. More than 100 remain unaccounted for. Armenian authorities say more than 3,000 of their troops died, while the total number of civilian casualties was around 150, according to official tallies from Armenia and Azerbaijan.

“There were many tragedies on both sides. The wounds are very deep,” said Natig Jafarli, an Azeri opposition politician who heads a research organization he says has been working to establish contacts between Azeris and Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh, with the aim of fostering some measure of reconciliation.

Each side blames the other for triggering last fall’s conflict, and while both are former Soviet republics, they are divided by culture, religion and allegiance to the region’s major powers. Azerbaijan is allied with Turkey, while Armenia shares strong bonds with Russia, which maintains military bases there.

The conflict over who should control Nagorno-Karabakh, around the size of Delaware, could also reignite if the two sides fail to build bridges to each other.

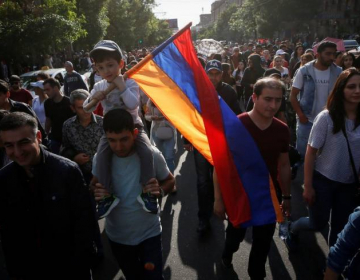

Many Armenians have already called on Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan to resign for having conceded to the truce, condemning it as an act of capitulation. Members of the Armenian diaspora in the U.S., Europe and elsewhere have warned Azerbaijan to grant equal rights and protection for Armenians who might opt to return to areas now under Azeri control.

Azeri officials accuse Armenian forces of using banned cluster bombs against some Azeri towns such as Barda during last fall’s conflict, a claim supported by a recent Amnesty International report.

Left, Azeri flags decorate downtown Baku, some with the slogan 'Karabakh is ours.'

Right, a picture of Azeri President Ilham Aliyev and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan hangs inside a car.

Each side also accuses the other of continuing to mistreat prisoners of war. Both deny the other’s claims.

Hikmet Hajiyev, chief policy adviser to Azeri President Ilham Aliyev, acknowledged that finding common ground is challenging, but the two sides have already agreed to work together to revive Nagorno-Karabakh’s tattered economy and strengthen trade and rail links, an important component of the peace deal. The deputy prime ministers of Armenia, Azerbaijan and Russia are expected to meet in Moscow on Saturday to begin discussions.

“In any military operation, winning the war is sometimes much easier than winning the peace,” Mr. Hajiyev said.

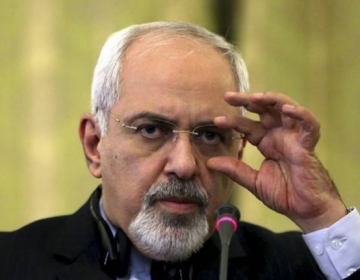

Hikmet Hajiyev, chief policy adviser to Azerbaijan’s president, said finding common ground between the two sides is challenging.

Ali Hajizade, a political analyst in Baku, said that without reconciliation between ordinary Azeris and Armenians, sustainable peace will be impossible. “This is an achievable goal, but this is not possible now,” he said.

Azerbaijan appears to have the upper hand in the peace process. Funded in part by oil wealth, its military capability is vastly superior to that of Armenia. Reclaiming territory lost to Armenia during the collapse of the Soviet Union has long been a goal for its leaders and enthusiasm for its territorial gains in Nagorno-Karabakh is palpable.

Celebrations have spread across Azerbaijan since the truce was signed and local media still boast of its triumph. At the immigration and baggage halls at Baku’s international airport, signs hanging on walls and above passport inspection booths greet arriving passengers with the declaration: “Karabakh is ours. Karabakh is Azerbaijan.”

“For the last 30 years, Azerbaijan’s social life, economic life, foreign policy, you name it, everything was dedicated to one problem only—Nagorno-Karabakh,” said Ahmad Alili, director of the Caucasus Policy Analysis Center, an independent think tank in Baku.

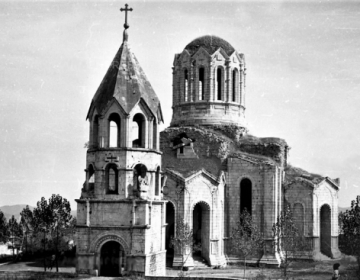

Baku's Alley of Martyrs, a cemetery and memorial dedicated to those killed by the Soviet Army.

In the Alley of Martyrs, the grave of a soldier who was killed in the 1992 war over Nagorno-Karabakh.

Those who lost loved ones in the conflict, though, are anxious not to see their sacrifice overlooked as the two countries begin working toward a lasting peace, he warns.

“The one thing that is left for the parents or wife of a fallen soldier is that the son or husband’s name is not forgotten,” Mr. Alili said.

During her last phone conversation with her son, Mrs. Budaqova told him to be careful. He told her that the day before their phone call, around Azeri 20 soldiers had been killed in Fizuli, a district that Azerbaijan reclaimed. Mr. Budaqov was headed there to help secure the area before their bodies could be collected.

As artillery fire rained down, he was caught in a crossfire. A bullet severed an artery in his leg and he bled out, his mother was told.

She and her sister mourn their loss in the living room that doubles as a shrine to Mr. Budaqov. Posters with his picture hang on the outside gate and railings, something other families that lost children in the war do, too. The walls inside are covered with photo collages of when he was a child, and when he first joined the military. His image adorns the face of a wall clock, which hangs next to one of his first army uniforms.

He wasn’t afraid to go to the front, Mrs. Budaqova said, adding that she believes the war was worthwhile if Azerbaijan reclaimed lost land.

“But if my son was still here, it would be much better,” she said.

Mrs. Budaqova and her sister live in a one-room flat in Baku that they have decorated with pictures of her son.

pia.az