The Armenia-Azerbaijan agreement provides an opportunity for the U.S. to develop a new regional policy focusing on conflict resolution and an inclusive platform for peacebuilding.

by Nurlan Mustafayev

The National Interest

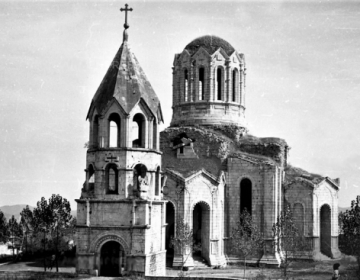

Europe's longest-running territorial conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan ended after forty-four-days of bloody fighting with the signing of a Russia-brokered trilateral Joint Statement on November 10, 2020. The agreement’s key consequences are the withdrawal of Armenia’s armed forces from Upper Karabakh (Nagorno-Karabakh) and seven adjacent districts of Azerbaijan and the right of return of all displaced persons (IDPs)—a critical impediment to regional stability in the past thirty years.

The emergent new regional order post-hostilities is based on an umbrella of Russian-Turkish security cooperation. Under this arrangement, a sizable Russian peacekeeping force was deployed in Upper Karabakh and alongside the land corridor connecting the region with Armenia. In addition, the joint Turkey-Russia peacekeeping center operates to monitor the cease-fire. It will be the first time in NATO’s history for its member state to engage in regional security monitoring in a former Soviet Union country.

Notably, the United States and France, as co-chairs of the OSCE Minsk Group—the mediation group entrusted to find a peaceful solution to the conflict—were absent in this critical regional diplomatic endeavor. It was hardly accidental. The U.S. disengagement, France’s perceived partiality, the diplomatic stalemate, coupled with the Minsk Group’s ineffectiveness in the past twenty-six years played a key role in this situation.

The United States did not have a consistent policy in the region under all three past U.S. administrations even though it has important security and economic interests, which include maintaining the strategic Northern Supply Route to Afghanistan via Azerbaijan and Georgia; promoting U.S. companies, trade and investments; preserving regional stability; preventing the resumption of frozen conflicts; and supporting democratic change and better governance as well as the international integration of Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia. The past U.S. administrations pursued some of these goals at the expense of others and without clear prioritization. As a result, it achieved some of its policy goals in regional integration, energy, trade, and investments. However, it failed in its most crucial goal of peaceful settlement of frozen conflicts.

The lack of consistent regional policy also led to contradictory policies towards Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia. The United States has focused on Georgia as the cornerstone of the U.S. approach toward the region. However, thanks to the pressure from the influential Armenian lobby in the U.S, it granted Armenia preferential treatment vis-à-vis Azerbaijan, such as diplomatic backing, increased security, and economic assistance—the platform of the U.S.-Armenia strategic dialogue. The past U.S. administrations pursued this preferential approach against the background of the ongoing, albeit frozen, Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict and Armenia’s opposite foreign policy orientation.

While all three recent U.S. administrations valued Azerbaijan’s contributions to the U.S. goals, such as regional stability, Afghanistan policy, energy projects, exports, the bilateral relationship remained relatively static. Despite increasing security assistance to Azerbaijan’s border security, the parties could not elevate their ties to a new level on par with Armenia and Georgia. It has created a sense of uncertainty in Azerbaijani society about U.S. impartiality in the conflict and its regional strategy.

Options for New Regional Policy

The success of the United States’ new re-engagement policy will largely depend on how it will deal with the reconciliation of Armenia and Azerbaijan. Given the end of the hostilities now, the United States needs to develop a coherent regional policy based on the priority of the permanent resolution of the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict and regional economic integration. Here are the six points of how the Biden administration can approach these complex issues in its new regional push.

First, the United States needs to shift away from its traditional policy of “conflict prevention” in favor of “conflict resolution” in the region. It requires strengthening the implementation of the Armenia-Azerbaijan agreement, which significantly overlaps with the “Basic Principles” proposed by the Minsk Group. U.S. policymakers should be aware that Azerbaijan as a state does not consider itself to be entirely viable without Upper Karabakh in terms of security, geography, and economy. Given such complexities, the conflict needs an incremental approach in negotiating numerous supplemental agreements to meet Azerbaijan’s critical national security needs and protect minority rights of ethnic Armenians (e.g., cultural autonomy) in Upper Karabakh. The Northern Ireland peace process overseen by various U.S. diplomats since 1995 is an example of how long and arduous a genuine reconciliation process can take between two nations.

Second, the United States needs to see the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict as a standalone issue separate from its worsening relationship with Turkey or Russia, NATO-Turkey, and Russia-Turkey, or Turkey-Armenia relations. Linking this conflict to geopolitics and external players, as advocated by some U.S. lawmakers and lobby organizations, will limit options for negotiation in the fragile peace process. It will also divert attention from the core issues—a reconciliation of Armenia and Azerbaijan, undertaking extensive post-war reconstruction work, including the return of IDPs.

Third, the United States should strive to be a neutral and impartial mediator and avoid the perception of appearing pro-Armenian in the conflict. The United States and Russia are the only global powers in the region that both Azerbaijan and Armenia still trust and accept. U.S. policymakers need to build on this trust instead of weakening it by calling for reviewing security assistance to Azerbaijan or recognizing the “Nagorno-Karabakh Republic” as a response to Azerbaijan’s recovery of its internationally recognized territories. Azerbaijani society will view such potential moves as profoundly unfair and as recognition of Armenia’s territorial claims, which will significantly reduce U.S. soft power and influence in shaping the region’s political future.

Fourth, the United States’ new regional engagement should continue supporting Azerbaijan-led regional energy and transport projects that link the South Caucasus to European and East Asia, especially Chinese markets. Mutual economic dependence and linking peace to economic opportunities will augment a chance for regional peace. For instance, in addition to standalone land corridors stipulated in the Joint Statement, the implementation agreement between Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Russia signed on January 11, 2021, envisages the unblocking of regional rail connections and building new interconnections, connecting the region’s economies. It will link Armenia to Iran, Russia, Turkish markets, and Azerbaijan to its Nakhichevan exclave and Turkey.

It is a substantial economic opportunity for Azerbaijan and Armenia—a land-locked country whose 85 percent of rail traffic used to pass through Azerbaijan before the start of the conflict in 1990.

Fifth, by applying its experience in Kuwait’s reconstruction, U.S. humanitarian assistance and participation of American companies will be essential in rebuilding the war-torn de-occupied areas—utilities, roads, housing, schools, medical facilities for almost 800.000 Azerbaijani IDPs, and Karabakh Armenians. The UN estimate of economic damage is about a staggering $53.5 billion, beyond the capacity and resources of a small country like Azerbaijan.

Six, common regional problems can no longer be dealt with in a piecemeal manner and through bilateral relations alone. Developing a joint strategic dialogue platform involving the United States, on the one hand, and Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Georgia, on the other hand, to regularly discuss security and economic integration issues would significantly advance the goals of a new U.S. regional policy. Such inclusive regional engagement would produce better coordination among regional countries, build more trust and make the permanent Armenia-Azerbaijan peace closer. Given Azerbaijan’s role as the regional integrator with the largest economy and multi-directional foreign policy, there is a need to elevate the U.S.-Azerbaijan relationship to strategic dialogue on par with Georgia and Armenia. In this respect, as the transport routes between Armenia and Azerbaijan are being restored, repealing Section 907 of the Freedom Support Act—a psychological barrier and highly unfair legislation—could start a new era U.S.-Azerbaijan relationship and contribute to the success of its new regional engagement.

Nurlan Mustafayev is a Baku-based specialist in international law and public administration. He works as a senior advisor on international legal affairs at the State Oil Company of the Republic of Azerbaijan. His views are his own and do not represent that of his employer. Follow him on Twitter @nmustafayev.

pia.az