Shahin Jafarli

Shahin Jafarli

Bakuresearchinstitute.org

On the night of November 9, 2020, a trilateral statement signed by the leaders of Russia, Azerbaijan, and Armenia ended the 44-day Karabakh war. Russian peacekeeping forces entered the conflict zone and began their mission on the new line of contact. This event led the victorious mood in Azerbaijan to gradually subside, to be replaced by anxiety. Currently, two-thirds of the territory of the former Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Region is under the control of the Russian army, and questions remain as to whether Azerbaijan’s sovereignty will be restored, when the peacekeeping operation will end, and what will be the status and the fate of the territory. In this regard, a retrospective look at how Russia has conducted peacekeeping operations in other ethnic and territorial conflict zones in the post-Soviet space, its relations with central governments and local separatist administrations, the models of de-escalation it has implemented, and the results of these operations may help to draw conclusions.

The Russian Federation’s establishment of peacekeeping forces, principles of their application, and rules of use are regulated by a special law. The law On the procedure for the provision by the Russian Federation of military and civilian personnel to participate in activities to maintain or restore international peace and security, adopted by the State Duma on May 26, 1995, was signed into law by President Boris Yeltsin on June 23 of that year. In addition, the principles of the use of Russian peacekeepers abroad are enshrined in the country’s Military Doctrine and Foreign Policy Concept.

Georgia: Peacekeeping operations in South Ossetia and Abkhazia

On June 24, 1992, after protests in the Autonomous Region of South Ossetia against the Georgian SSR Supreme Soviet’s declaration of Georgian as an official language had escalated into an armed conflict, Russian President Boris Yeltsin and Georgian President Eduard Shevardnadze met in Sochi and signed an agreement on the principles of the conflict’s resolution. The Sochi agreement included clauses calling for a ceasefire; the withdrawal of the armed forces of the conflict parties; the release of local self-defense forces; the establishment of a Joint Oversight Commission, including representatives of the three sides, overseeing the ceasefire and providing security; a military observer group; and the transfer of control of the Joint Forces to the Commission for peacekeeping. The Joint Oversight Commission was designed to deal with economic and administrative issues, and the Joint Forces was designed to address security issues.

In other words, the idea was for Russia to conduct a peacekeeping operation in South Ossetia, not on its own, but jointly with both sides of the conflict. Accordingly, on July 9, 1992, a joint Russian-Georgian-Ossetian peacekeeping force was deployed in the region, ending military operations. The Joint Forces consisted of three battalions — from Russia and Georgia, and from the Russian Autonomous Republic of North Ossetia instead of South Ossetia. This meant that, in fact, two of the three battalions represented Russia. The peacekeeping forces had to work together under the command of a single headquarters and one officer from each of the three parties, and joint checkpoints had to be set up on the roads to inspect and disarm the local population. In December 1994, at a meeting of the Joint Oversight Commission, it was decided to transfer all peacekeeping forces to the command of Russian General Anatoly Merkulov. The movement of heavy military equipment by Georgian and Ossetian forces was restricted. Only the Russian military could use heavy equipment in the area.

This history shows that the Sochi agreement actually legitimized Russia’s military presence in South Ossetia, on Georgian territory, in the name of peacekeeping, and led Russia to monopolize the conflict resolution process. The Georgian side was expected to participate in the peacekeeping operation on an equal footing with Russia, but Russia gradually took over control and the decision-making mechanisms on all issues in the region. The agreement’s humanitarian clauses were not implemented. Although formal meetings were held and protocols were signed, the Joint Oversight Commission failed to function effectively, and clauses on the return of refugees and the reconstruction of the region remained on paper. Conditions were not created for the return of Georgians who had fled their homes in the zone controlled by the Russian peacekeepers.

After Vladimir Putin came to power in Russia in 2000 and Mikheil Saakashvili in Georgia in 2004, tensions in bilateral relations gradually increased, affecting the situation in the conflict zones. In December 2000, the Russian government made a unilateral decision to introduce a visa regime with Georgia, but the decision did not apply to residents of South Ossetia and Abkhazia. Although Moscow explained its decision as a measure to prevent the entry of Chechen militants and terrorists into Russia, Shevardnadze’s government believed that the goal was to force him to abandon his demand that Russian military bases leave Georgia by the end of 2003. After Saakashvili came to power with a promise to restore the country’s territorial integrity, the parties began gradually moving towards war. In late 2006 and early 2007, the General Staff of the Russian Armed Forces drew up a plan approved by the political leadership for the possibility of an attack by Georgian government forces on South Ossetia. Putin later stated that during the war in August 2008, they acted in accordance with this plan. On August 26, immediately following the brief war (August 8-12) which ended in Georgia’s defeat, Russia recognized South Ossetia and Abkhazia as independent states.

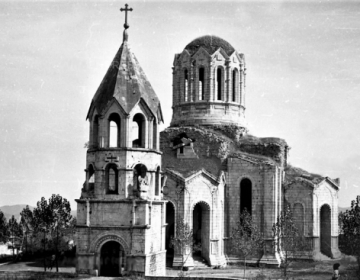

During the Soviet period, another autonomous administrative-territorial unit within the Georgian SSR was the Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic of Abkhazia. As in South Ossetia, separatism in this area arose at a time when the Soviet state had not yet collapsed but the central government was weakening. In March 1989, the Abkhazians decided to leave Georgia and become an allied republic within the USSR. In July of that year, the first armed clashes between Abkhazians and Georgians took place resulting in casualties, and then the scale of the conflict escalated, leading to a war that killed thousands of people on both sides and caused the Georgian population to flee the region. It is interesting to note that according to the 1989 census, only 17% of the population of the Abkhazian SSR were ethnic Abkhazians, while Georgians were the largest ethnic group with 45%. Abkhazia’s strategic importance is enhanced by its location on the Black Sea coast, and this is largely the reason for Moscow’s support for ethnic minority separatism in the conflict. In October 1990, while the USSR had not yet collapsed, Georgia held democratic elections bringing nationalists to power who were determined, under the leadership of Zviad Gamsakhurdia, to move away from Moscow and turn the country to the West.

In the first phase of the conflict, the Russian government sought to present itself as a neutral mediator and presented itself as seeking solutions within the framework of Georgia’s territorial integrity. In Gudauta in July 1993, with the mediation of Russia, the Georgian and Abkhaz governments reached an agreement on a ceasefire and the demilitarization of the conflict zone. In accordance with Georgia’s demand, Russia agreed to conduct this process under the supervision of international observers, and in August, the UN Security Council established an observation mission in Georgia. However, in September 1993, the Abkhaz took control of the city of Sukhumi and the entire territory of the former Autonomous Republic with the active participation of volunteer militants from the North Caucasus republics of the Russian Federation, including Cossack groups. At that time, the situation in Georgia was also critical, with armed supporters of former President Gamsakhurdia seizing territory in western Georgia and announcing a provisional government in the city of Zugdidi. As a result, Shevardnadze was forced to seek help from Russia and apply for membership in the CIS, to which Georgia was admitted in December 1993. In June 1994, by a decision of the CIS Council of Heads of State, CIS Collective Peacekeeping Forces were deployed to Abkhazia consisting entirely of Russian troops. The deployment of 50 UN military observers did little beyond gaining international legitimacy for Russia’s peacekeeping operation. The main peacekeeping headquarters and command were located in separatist-controlled Sukhumi, while the deputy commander’s headquarters were located in the city of Zugdidi, which had been recaptured from Gamsakhurdia’s supporters. Although there were agreements providing for the return of Georgian refugees, Abkhazian armed groups prevented this, a small number of returnees were attacked, and Russian peacekeepers did not intervene, claiming that they could not perform police functions.

On November 26, 1994, after the arrival of the peacekeepers, the Supreme Soviet of Abkhazia declared Abkhazia an independent, sovereign, democratic state, and in December, Vladislav Ardzinba was sworn in as President. Although Russia unofficially supported separatism at the time, it did not support independence, preferring the federalization of Georgia. For example, the Protocol on the Resolution of the Georgian-Abkhazian Conflict, which was initiated in 1995, provided for Abkhazia to become a federal subject of Georgia. Even though the Abkhazians opposed it, on the basis of a Georgian proposal, the CIS summit in 1996 decided to ban trade, economic, financial, transport, and other relations with Abkhazia, i.e. to impose sanctions on Abkhazia. Russia organized a visit by Abkhaz leader Ardzinba to Tbilisi and decided to establish a joint Georgian-Abkhazian commission. However, these attempts failed to yield results, and in 1999 Abkhazia held a referendum on independence, refusing to discuss status. In March 2003, there was new activity aimed at the resolution of the problem, and the presidents of Russia and Georgia began the so-called Sochi negotiation process. However, in November of that year, as a result of the Rose Revolution in Georgia, Saakashvili came to power and the process ended. Saakashvili accused Russia of pursuing a policy of annexing Abkhazia. Georgia’s new government changed the format of the negotiation process and the peacekeeping operation, trying to limit Russia’s role, but failing to do so. In 2008, in response to Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic integration policy, a referendum on joining NATO in January 2008, and an official application for membership, Russia lifted sanctions against Abkhazia in March, and in April Putin ordered the establishment of direct relations with Abkhazia and South Ossetia. The peacekeeping contingent in Abkhazia was strengthened, first with an airborne battalion of 525 people, and then in May with a 400-strong unit of the railway troops. After the August 2008 war, Russia recognized Abkhazia as an independent state, along with South Ossetia.

Moldova: The peacekeeping operation in Transnistria

In Moldova, separatism on the left bank of the Dniester River, as in South Ossetia, began with language disputes. The proclamation of Moldovan as the state language by the Supreme Soviet of the Moldovan SSR in August 1989 was met with protests in Transnistria, and a year later a meeting of local deputies declared the establishment of the Transnistrian Soviet Socialist Republic of Moldova. The armed conflict began in March 1992, and the involvement of the 14th Soviet Army stationed in the area resulted in the defeat of government forces. In desperation, the Moldovan government was forced to sign an agreement with Russia in July 1992, On the principles of a peaceful resolution of the armed conflict in Transnistria, after the commander of the 14th Army, the famous General Alexander Lebed, threatened to take his army to Chisinau. In accordance with the agreement, a trilateral peacekeeping force was established, which included a total of 12 battalions — 6 from Russia and 6 from the parties to the conflict. A security zone 10-20 km wide and 220 km long was created on both banks of the Dniester River. The peacekeepers were led by a Joint Oversight Commission consisting of 6 members from the parties to the conflict (3 from each) and 6 from Russia. Joint checkpoints were set up on the roads. Although the signed document did not provide for the involvement of the 14th Army in peacekeeping operations, that group of troops was not withdrawn from the area. General Lebed, in fact, behaved as the head of the territory, and even though he was a Russian citizen, he was elected a member of the local parliament. At the end of 1994, after the stabilization, the Russian government decided to halve the peacekeeping force.

Russia currently has two military contingents in Moldova: the Russian Troop Task Force (formerly the 14th Army) and the peacekeepers. Ten military observers from Ukraine, who acted as mediators in the 5+2 format, were also involved in resolving the conflict. In the 5+2 format, the two parties to the conflict are represented along with Russia, Ukraine, and the OSCE as mediators, and the European Union and the United States as observers. At the 1999 OSCE summit in Istanbul, Russia pledged to withdraw its army (the task force) and weapons from Moldova by the end of 2002, but has so far failed to do so. Although the Moldovan government has repeatedly suggested replacing Russian peacekeepers with an international contingent, Russia has refused.

In 2003, Dmitry Kozak, the deputy head of Russia’s presidential administration, drafted a memorandum to resolve the conflict. Kozak’s plan, which called for the federalization of Moldova, the transition of Transnistria and Gagauzia into federal subjects, the maintenance of Russian forces there for 20 years to guarantee order, and Moldova’s neutrality and demilitarization, was initially approved by Moldovan President Vladimir Voronin, but on the night of November 24, 2003, when he was scheduled to sign the document, he reversed his decision at the last moment. Russia claims this reversal occurred under pressure from the West. Recently, in 2019, Kozak proposed another, very similar peace plan. Although the plan was expected to be signed at the Russian embassy in Chisinau by pro-Russian socialist President Igor Dodon and the leader of the ruling Democratic Party, the oligarch Vladimir Plakhotnyuk, history repeated itself: Plakhotnyuk refused to sign the document at the last minute.

Currently, the conflict resolution process has stagnated. Although Moldova raised the issue of the withdrawal of Russian troops and peacekeepers immediately after the election of the new president, Maia Sandu, Moscow has made it clear that it will not comply. Negotiations in the 5+2 format have not been held since 2018, and the activities of the Joint Oversight Commission have virtually ceased.

Russia’s political weapon: Passports

There is a model that Moscow has so far applied in all conflict zones in the post-Soviet space where it conducts peacekeeping operations (except Nagorno-Karabakh): the distribution of Russian passports to the local population. Dmitry Medvedev, Russia’s president during the war in South Ossetia, described the military intervention as a response to the deaths of Russian citizens and peacekeepers in a Georgian attack. “When the rocket launchers went off, the tanks started firing, and I was told about the deaths of our citizens, including our peacekeepers, I ordered a response without a moment’s hesitation.”

The Russian State Duma passed the bill On Russian citizenship in May 2002, which was approved by the Federation Council in May, and the distribution of Russian passports to residents of South Ossetia and Abkhazia began in June after the law was signed by President Putin. However, providing for individual applications by Abkhazians and Ossetians for Russian citizenship was a process that began before the law was passed. At present, at least 95% of the people living in South Ossetia, which Russia recognizes as an independent state, and 140,000 of Abkhazia’s 245,000 residents are Russian citizens, and the distribution of passports continues.

In September 2006, the Russian government opened a Russian Citizenship Registration Center in Tiraspol, the administrative center of Transnistria. Residents wishing to become Russian citizens submit their documents to the center. However, holders of Moldovan and Ukrainian passports face difficulties in obtaining Russian citizenship. The separatist leadership appealed to the Russian government to remove this obstacle and create conditions for the transition to Russian citizenship in a simplified format. At present, 220,000 Transnistrians have Russian passports, 150,000 have Moldovan passports, and 100,000 have Ukrainian passports. Local youths who are Russian citizens are called to serve in the Russian peacekeeping forces.

Before annexing Crimea, Russia was already issuing passports there. In 2008, Ukrainian Foreign Minister Volodymyr Ohryzko stated that the Russian Consulate General in Simferopol was distributing passports to Crimean residents. Russia is not currently conducting a peacekeeping operation in the conflict in eastern Ukraine, but it is granting citizenship to residents of the region. On April 24, 2019, President Putin signed the Decree on defining, for humanitarian purposes, the categories of persons entitled to apply for admission to Russian citizenship in a simplified format. According to the decree, persons permanently residing in certain areas of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions of Ukraine (territories beyond the control of the Ukrainian state) have the right to apply for Russian citizenship in a simplified manner under Article 14 of the law On Russian citizenship. The appeals are considered for 3 months.

It is necessary to highlight Article 14 of the law On Russian citizenship. Part 1 of the article, entitled Admission to citizenship of the Russian Federation in a simplified format, states: “Stateless persons who have reached the age of eighteen and have legal capacity have the right to apply for admission to citizenship of the Russian Federation in a simplified format <…> if these persons had USSR citizenship, lived in and [currently] live in states that were part of the USSR, and did not receive citizenship of these states.” In addition, according to the law, citizens of Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova, and Kazakhstan can obtain Russian citizenship in a simplified format.

Conclusion

There are similarities between the onset, development, and outcomes of all the ethnic-territorial conflicts investigated in this article. They share both similarities and differences with the causes, progression, and consequences of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. Let’s take a look at these similarities and differences:

First of all, it should be noted that in each of the conflict zones where peacekeeping operations took place, there were Soviet military bases during the Soviet era. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, these military units automatically became part of the Russian Armed Forces, i.e. they simply changed their names. For example, in Tskhinvali, the administrative center of South Ossetia, there was the 37th Engineering and Fortification Regiment of the Transcaucasian Military District of the USSR Armed Forces and the 292nd Special Helicopter Regiment; in Sukhumi, the administrative center of Abkhazia, the airborne battalion, in Gudauta the air base, and in the village of Eshera the military seismological laboratory; and in Transnistria the 14th Army. After the start of military operations in those areas, these military units assisted local separatist forces, which is why the central governments, trying to ensure territorial integrity, lost those wars.

The 366th motorized guard regiment of the Transcaucasian Military District was deployed in Khankandi (Stepanakert), the administrative center of the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Region of the Azerbaijani SSR, and the military equipment, and even the personnel, of that unit were used by the Armenian side in the conflict. After the attack on Khojaly and the massacre on February 26, 1992, the Russian command moved the 366th Regiment from Karabakh to Georgia, but during the evacuation a large number of the regiment’s military equipment and weapons fell into the hands of local Armenian forces, and some soldiers and officers (including those of Armenian descent) remained in Karabakh.

When Russia launched a peacekeeping operation in South Ossetia, it involved the parties to the conflict: a Joint Oversight Commission, consisting of representatives of the three parties, was created to resolve local governance and economic issues, as well as joint forces to resolve security issues. This model has been applied in the Transnistrian region, where trilateral peacekeeping forces and joint checkpoints have been established, and a Unified Oversight Commission consisting of the parties to the conflict and Russia has been created to manage them. Abkhazia had a peacekeeping force composed entirely of Russian troops under the CIS flag, but it also had a headquarters in Georgian-controlled territory. At the same time, the UN was involved in the peace process.

According to the trilateral statement of November 10, 2020, the peacekeeping operation in Nagorno-Karabakh is completely under the authority of Russia for 5 years; Azerbaijan, local Armenians, and Armenia are not involved in this process. A peacekeeping contingent consisting of 1,960 Russian armed military personnel, 90 armored vehicles, and 380 vehicles and special equipment has been deployed in Nagorno-Karabakh along the line of contact and the Lachin corridor. A second state, Turkey, is also involved in the ceasefire oversight mechanism. The Turkish and Russian military work together at the Peacekeeping Center. The center has no authority to resolve political or humanitarian problems or to ensure security. An Interdepartmental Center has been established by a Russian presidential decree to resolve humanitarian issues and restore infrastructure in the area of the peacekeeping operation. Various Russian ministries and government agencies are represented at the center in Khankandi (Stepanakert). This agency is, in fact, a mini-model of the Russian government in Karabakh, and the Republic of Azerbaijan does not participate in the activities and decisions of the center.

After the war in South Ossetia and Abkhazia and the defeat of the government forces, the local Georgian population was forced to leave. Although the Russian-brokered ceasefire and settlement agreements provided for the return of refugees, in practice that was impossible. The reason is clear: the population affiliated with the Georgian state could create problems in the seizure of those territories from Georgia. Prior to the conflict, Georgians made up 45% of the population of Abkhazia and 30% of South Ossetia. Article 7 of the November 10th Karabakh ceasefire declaration states that internally displaced persons and refugees are to be allowed to return to the territory of Nagorno-Karabakh and the surrounding regions under the supervision of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. The question of fundamental importance for Azerbaijan is whether Azerbaijanis living in the areas where the peacekeeping operation is in place (Khankendi [Stepanakert], Khojaly, etc.) will be allowed to return there. We don’t know yet, but only 5 months have passed since the signing of the document, and it is possible that this issue will come up in the near future.

Russia’s issuing of passports to locals during peacekeeping operations served to deter central governments from using military force and created additional pressure on them. In this way Russia shows that it does not intend to leave those territories and will not comply with such demands. One matter of concern in Azerbaijan since the signing of the November 10 declaration is whether Moscow will implement the same practice in Karabakh. There is a justification for this from a purely legal point of view. According to the law On Russian citizenship, able-bodied, stateless persons who have reached the age of 18 have the right to apply for citizenship of the Russian Federation in a simplified format if they were citizens of the USSR, lived in states that were part of the USSR, or currently live in such states but have not received citizenship. It is true that Armenians living in Nagorno-Karabakh have Armenian passports, but if Russia decides to issue them passports, it may ignore this fact. It is worth mentioning that a representative of the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs is also represented at the Humanitarian Center established by the Russian government in Nagorno-Karabakh.

Of course, all this does not mean that Russia will repeat the policies it implemented in Abkhazia, South Ossetia, and Transnistria in the same way in Nagorno-Karabakh. (Although the announcement of Russian as the second official language of Nagorno-Karabakh might indicate that.) However, there is a need to study Russia’s experience in peacekeeping operations, the models it has used so far in conflict zones, and draw conclusions. The state of Azerbaijani-Russian bilateral relations will have a direct impact on the development of events and the future of Nagorno-Karabakh.

***

Shahin Jafarli is a noted Azerbaijani journalist and political commentator. He received his MA in Political Science from the State Academy of Public Administration under the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan .

pia.az