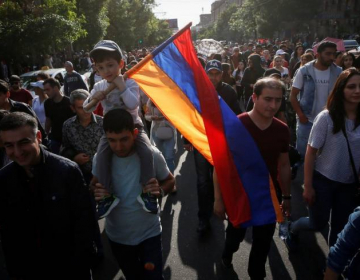

At a rally on March 1, Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan announced his plans to return to a semi-presidential form of government, which he considered ineffective when he tried on the post of prime minister in 2018. At that time, the 2015 constitutional reform came into force, which ensured the transition from a semi-presidential to a parliamentary form of government.

Pashinyan, who was satisfied with the form of a parliamentary republic, since he did not limit his actions to the intervention of the president. The latter has now become a nominal figure performing the role of an arbiter in the face of open confrontation between the parliamentary majority and the opposition. President Armen Sarkissian, elected by the ruling parliamentary majority, has so far diplomatically smoothed out Pashinyan's confrontation with his rivals from the past, ex-President Robert Kocharian and his supporters. However, the 44-day Karabakh war pushed Armenia to the brink of a civil war, where it is more and more difficult for the president-arbiter to smooth over the contradictions. The situation requires broader presidential powers to make non-declarative and binding decisions.

“The Constitution, which was adopted in 2015 and entered into force in 2018, revealed a huge number of shortcomings for us, including it conceals risks for creating crisis situations. We believe that the transition to a semi-presidential form will be one of the best options,” said Pashinyan, who considers this approach the best way out of the crisis.

What prompted Pashinyan to this decision in conditions when he had a working tandem with the president, and when the prime minister, as the street shows, continues to enjoy the trust of the majority of the country's citizens, despite the heavy defeat from Azerbaijan in last year's war? The rally on March 1 was impressive in terms of the number of participants and to date did not leave the opposition a chance for revenge, which it cherishes since the signing of the Russian-Armenian-Azerbaijani peace statement on November 10, 2020.

If you look at the map of Armenia from a bird's eye view, you can see the constant redeployment of political forces in the public field, striving to capture or keep the ruling Olympus in the face of possible early parliamentary elections or, at worst, the next elections in 2023. The elections could put an end to a shaky situation, and there is a threat of Pashinyan's defeat, his ongoing reforms and Armenia's return to an authoritarian paramilitary form of government led by former hawks. Given the current political structure of state power in Armenia, the Prime Minister's associate, nominal President Sargsyan, will not be able to do anything to prevent Armenia from falling back into the hopeless past. If the opposition wins the parliamentary elections, in 2025, after the seven-year term of Sargsyan's presidency, the parliamentary majority of Pashinyan's opponents will elevate their protege to the presidency, which will ensure complete harmony of parliamentary and presidential power.

Two versions come to mind about Pashinyan's decision to return to semi-presidential rule. The first can be called a safety net and it involves the transfer of powers to Sargsyan, which provide him with the role of a full-fledged head of state, heading the armed forces and capable of dissolving parliament and so on. In the case of the incapacity of the prime minister (terrorist attack, state of emergency), the president takes control of the situation and ensures the continuation of the political course.

The second is proactive. Pashinyan's term expires in 2023 or may be earlier in the event of early elections, that is, he may not complete the transition of Armenia from a military track to a peaceful one and ensure the country's regional non-confrontational coexistence and its openness to peace. In this difficult party, Pashinyan could decide to move to the presidency with new broad powers, which would ensure a long-term continuation of the business he had begun. If this happens this year, it will guarantee him a reign until 2028.

The expansion of the powers of the president may take place already before the national referendum. “Before the referendum itself, the parliament will be able to amend some articles of the Constitution, which do not require a popular vote,” the prime minister said at a rally on March 1.

However, for the election of Pashinyan as president, Sargsyan's resignation is necessary. It is quite possible. Since September 2020, the president's respiratory illness has been announced three times. From the beginning of January to mid-February of this year, Sargsyan was treated for a long time in London for coronavirus (according to the official version), and during the last political crisis the other day he fell ill again. Is not it the basis for health care?

Reference

Under the semi-presidential model (France), the president, as in the first case, is the head of state, but he is not the head of government and does not hold the post of prime minister. The President has the most important powers that allow him to influence the government. The essence of the semi-presidential model boils down to a strong presidential power, with a somewhat lesser degree of separation of powers than in presidential republics:

the president can preside over government meetings;

the president has the prerogative of approving decrees and decrees adopted by the government;

the president has the right to veto laws passed by parliament;

the president dissolves parliament;

the president is the supreme commander in chief;

the president determines the domestic and foreign policy of the state;

the president has the right to impose a state of emergency in the country. (turan.az)

pia.az